Tested to the limit - Animal testing laws and the power of the cruelty-free consumer.

- Riley Forson

- Jan 4, 2022

- 10 min read

© The Independent

Introduction:

Animal testing refers to procedures performed on living non-human animals for the purposes of: (i) biological research; (ii) assessing the efficacy and efficiency of new drugs, detergents, cosmetics and other consumer products; and (iii) assessing the safety of such consumer goods for human consumption or benefit. In the last few decades, testing on animals has become increasingly controversial. With legislation in place in the UK and Europe to reduce the use of non-human animals in scientific testing and the growth of new technologies which could replace their use completely, many now believe that the time has come to completely remove animal testing from modern society. In a time where, as a society, we are focused on off-setting our negative impacts, the ability for consumers to make informed choices and with the new concept of animal testing off-setting, society should be in a position to challenge the practice of testing on animals and secure the end to the use of animals in science.

Testing times for animals: what actually is animal testing:

There are different types of tests that animals are used for, including: (i) basic research; (ii) genetic modification; and (iii) regulatory testing.

Basic research:

Basic research is still the most common type of testing where animals are used to progress scientific understanding in the 21st century; it is the same type of research used by the likes of Galen (129-217 AD), the “Father of Vivisection”, who conducted animal experiments to further his teachings on anatomy, biology and pharmacology. In the unfinished novel from 1627, New Atlantis, by Francis Bacon, Bacon proposed to open “parks and enclosures for all sorts of beasts and birds which we use…for dissections and trials; that thereby we may take light what may be wrought upon the body of man”.

Genetic modification (“GM”):

GM is where animals are bred with specific genes removed or inserted, the researchers focus on the impact of these genes and how this may benefit human life.

Regulatory testing:

Cruelty Free International (“CFI”) explains that regulatory testing is standardised testing designed to see if medicines, chemicals (including paints, dyes, inks, petrol products, solvents, tars and waste materials), pesticides, biocides, food additives, cosmetics and other products are safe for use, and that they do their job effectively. Often this is where animals are forced to inhale products, have them inserted into their systems, rubbed on their skin before being killed to see the internal impacts.

Animal testing facilities:

Animal testing facilities are not appropriate places for any animal, particularly now that we increasingly understand the complex cognitive and emotional capacities of all animals used in testing.

For example, CFI found from an undercover investigation at Imperial College London in 2012 that rats were restrained while a long tube was repeatedly forced down their throats and substances injected directly into their stomachs. Similar investigations have taken place at Cambridge University by CFI due to the use of sheep being tested for Batten’s and Huntingdon’s disease. Others were forced to run on treadmills to avoid electric shocks until they were exhausted. Similarly, CFI undertook an undercover investigation at SOKO Tierschutz at Laboratory of Pharmacology and Toxicology in Germany and found "shocking" levels of animal suffering that CFI believe breach EU and German animal testing laws - Jane Goodall referred to this as "some of the worst abuse I've ever seen on testing with animals”. Video footage from a whistleblower at Vivotecnia in Madrid shows "young monkeys, physically restrained, no sedation provided to reduce their anxiety; monkeys slapped, their fur pulled and sworn at for struggling. We see rabbits struggling against their restraint devices, falling out and suffering serious spinal injuries.”

© HSI US

Animal testing and the progression of the law:

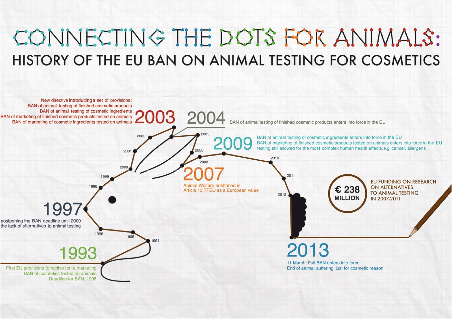

In 2003, a new European Directive was introduced and set out provisions banning the testing of finished cosmetic products on animals and of marketing of cosmetic ingredients tested on animals; the ban became effective in 2004. Following animal welfare being enshrined in Article 13 of the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union, in 2013 a full ban entered into force to end animal suffering just for cosmetic reasons, this was when Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes became effective legislation. The Directive harmonised animal research legislation across Europe and each Member State had to transpose the minimum standards of the Directive, but was free to legislate beyond the de minimis set out in the Directive. The Directive sets out at Article 1(1)(a) and Article 4, the legal requirement to implement the 3Rs - replacement, reduction and refinement: replace animals with non-animal methods where it is scientifically possible; refine practices to reduce suffering, distress and lasting harm; and reduce the number of animals used while still achieving scientific progress.

Article 5 makes it clear what procedures are acceptable and pure cosmetic improvement is not a legal procedure. However, there is a flaw in the law when it comes to Botox. In 2018, CFI found that 400,000 animals were killed in botox poisoning tests, known as LD50 tests - a test to determine how high a dose of the tested preparation is necessary for 50% of animals tested to die. Botox preparations can be legally tested in the EU, as Botox can be used for medical purposes, as well as cosmetic ones. While it would be illegal to test solely if the Botox is for cosmetic purposes, one test labelled as for medical purposes enables this ban to be completely undermined.

In the United Kingdom, the laws on use of animals in experiments is set out in the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 (“ASPA”), whereas the ASPA 1986 Amendment Regulations 2012 (“ASPA Amendment”), which came into force from 2013 after EU amendments to the 1986 Act were transposed, focuses on use of animals in testing and amends ASPA. Under the amended ASPA, s.1(1) a “protected animal” is one which is any living vertebrate other than man and any living cephalopod. Unlike in other legislation, where a “protected animal” is one that individuals strive to keep safe from harm, a “protected animal” under s.1 ASPA is one which can be used in animal testing. Under s.2(1) ASPA is “any procedure applied to a protected animal for a qualifying purpose which may have the effect of causing the animal a level of pain, suffering, distress or lasting harm…” A “qualifying purpose under the legislation is s set out at s.1A(a)-(b) as being “applied for an experimental purpose” or it is applied for “an educational purpose”. Section 2C(10) licences can be revoked where there is a change which “may have a negative effect on animal welfare”, but “negative effect” is left undefined and sufficiently vague, as is the concept of “animal welfare”, both which allow for exploitation of the animals used in experimental settings. The Government also amended ASPA to include s.2A which sets out the 3Rs.

ASPA barely focuses on the real subjects of animal testing and instead focuses mostly on the granting of licences and the rights of the Secretary of State; unfortunately, this is not unusual for laws that are meant to be focused on animals. Similarly, the statistics below call into question how closely the 3Rs are really being committed to or progressed in the United Kingdom.

© EU Commission

Putting the statistics under the microscope:

In the British Government’s Annual Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain, 2020, the key results that the report highlights at the start are that there has been a 15% decrease in animal testing since 2004, which would suggest that the European ban and the domestic legislation has had some positive impact. But, the report still makes for shocking reading when one gets past the graphs and highlighted virtue signalling facts.

The reality contained in the report for those who bother to read beyond the highlights, was that in 2020, 2.88 million procedures were carried out in Great Britain involving living animals, with around half of these being experimental procedures (for basic research, development of treatment, safety testing pharmaceuticals, surgical training and species protection”. The report notes that “the total number of procedures involving specially protected species has actually increased over the past decade from 16,000 in 2011 to 18,000 in 2020. Most notably the increase in the use of horses which increased by 29% and the number of experimental procedures that has used cats has increased 11% on last year, with 150 experimental procedures on cats in 2020; the use of dogs also increased by 3%, but has decreased 5% over the last 10 years. The report also notes that 2 endangered species were tested on and of the 1,700 primates used for first time experiments in 2020, all marmosets, tamarins and rhesus monkeys were born in the UK, but 98% of cynomolgus monkeys were born in Africa or Asia; given that the report notes that 2,069 procedures were undertaken on cynomolgus monkeys and only these species were used for regulatory testing, as well as scientific testing (as cynomolgus monkeys share a 93% DNA similarity with humans), one would assume that at least 1,000 cynomolgus monkeys have been, at some point, stolen from the wild or been held in breeding centres abroad to be shipped to England for testing.

In the European Commission’s Scientific Conference Report - Towards the replacement of animals for scientific purposes, one of the key note speakers of the first session, on how transparency can accelerate the transition to non-animal science, Pierre Deceuninck, Data Scientist in the Chemical Safety and Alternative Methods Units of the EC’s JRC, stated that in 2008 under the previous Directive governing animal testing, that the 27 EU Member States reported 12 million animals used for scientific purposes. In 2017, the report was of 9.4 million animals used for the first time in scientific procedures, a decrease of 20% and that 61% were mice, 30% fish, 12% rats and 6.4% other mammals.

Ultimately, although there is a decrease in the use of animals being used in testing procedures, as is required by law, the number is still staggeringly high and the rise in the use of primates, cats, dogs and horses should be setting red flags waving and alarm bells ringing given what science knows of the cognitive abilities and sensitivities of these animals. The extremely high levels of mice and rats used should also be a concern as we now understand that these small animals also possess considerable emotional and mental intelligence.

© The Standard

Testing offsetting:

The morality of animal testing has become increasingly controversial as new non-animal methods are developed by scientists. The development of “organs-on-a-chip” which use computer microchips to mimic the “microarchitecture and functions of living human organs”, is just one example of how animals could be retired from the testing arena. Similarly the Canadian Centre for Alternatives to Animal Methods, aims to “develop, validate and promote non-animal, human biology-based platforms in biomedical research, education and chemical safety testing”, as their research has found that 95% of drugs tested on animals have failed human clinical trials, showing that the move away from animal testing may provide more effective and reliable results in testing.

One concept that has recently come to light is the concept of animal testing off-setting. This was a concept first discussed on the Paw & Order Podcast hosted by Jessica Scott-Reid and Camille Labchuk, both animal rights advocates, while they interviewed Dr Charu Chandrasekera, founder of the Canadian Centre for Alternatives to Animal Methods. During the interview, Camille explains that she found it difficult that her Covid-19 vaccine would have been tested on animals and to mitigate this negative of her being vaccinated with a drug tested on animals, she was going to donate to Dr Chandrasekera’s programme. This then created the concept of animal testing off-setting, where one donates to organisations which are progressing non-animal alternatives which could eventually phase out the use of animals in science.

As Dr Chandrasekera explained, testing-offsetting is the best way to fight the “archaic system that demands animal testing”, as it is much harder to avoid and is often an area where individuals lack the ability to make a choice to avoid animal exploitation, as they can with their diets or fashion statements. Often the development of alternative means of testing require considerable amounts of funding and this is a positive means of off-setting the negative impact of being a consumer of medical products tested on animals and helping to provide the positive impact to institutions which will then help to phase out the use of animals in science and testing.

Leaping bunny approved:

While avoiding medical products tested on animals often is a harder task, what is easier is to make changes to your consumer habits with regards to your cosmetics. No animal should be made to suffer for the price of what is essentially vanity and ignorance, as is shown by the HSI Save Ralph video and campaign: https://www.hsi.org/saveralphmovie/.

It is so simple to avoid cruelty based products; companies which pay the PETA licensing fee of $350 yearly and sign the statement of assurance that they do not test on animals, will be able to display the PETA bunny sticker. The Leaping Bunny and CFI have recently merged, but their stickers will also appear on products as markers of cruelty-free brands.

Alternatively, if the company cannot afford the licensing fee, there are cruelty free databases, such as this one hosted by PETA: https://crueltyfree.peta.org/. PETA also hosts a database showing the companies which do test on animals.

By making a small decision to change to a cruelty free brand this not only helps the animals that are currently in the testing environment, but also demonstrates to brands that their ethics are not a la mode and will encourage them to make positive changes, as Forbes stated in 2019, if a company is not at a customers’ disposal, they become disposable.

Therefore, use your consumer power to show non-cruelty free brands that the world is ready to dispose of them until they make positive changes for animals.

© Ethical Elephant

Conclusion:

What is clear is that despite legislation in place in the UK and Europe, that considerable numbers of animals are still suffering in testing centres, which are unnatural and cruel environments; worse still, that many of them are in clear violation of the law and should be held accountable for this. As testing on animals becomes more controversial as we continuously learn more about the cognitive and emotional capacities of the animals that are the subjects of these tests we must increase the pressure on the implementation of the 3Rs and campaign for the end of animals as test subjects. With new technologies available and the ability for everyone to make informed cruelty-free choices where it is possible and to off-set their negative impact where their consumer choices are curtailed, there seems to be a perfectly logical way to stop testing on animals and end their suffering.

Comments